|

Part 6b -

SINGPORE

[cont...]

’See you at Raffles’ :

catch phrase in the 1930’s era

15.3.07

Another amazing breakfast, I estimated 80 different dishes including 4

kinds of lychee. We didn’t even know there were

4 kinds of lychee.

Picked up at hotel [did I mention that's Raffles?]

for a Round the Island tour, excellent guide – Philip. First stop is

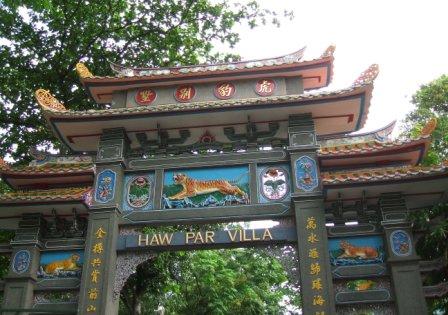

Haw Par Villa, a strange pleasure garden laid out by two wealthy

brothers to depict the ten stages of hell and other assorted goodies.

Later as they travelled the world, they added a statue representing each

place so among the Buddhist tableaux we come across a pair of black

swans [Perth,

Australia] and the Statue of Liberty. Everything seems to be made of cheap

plaster and is garishly painted. The stages of hell are lurid and

bloodthirsty, each scene out-doing the last for graphic gruesomeness.

There is a car made for one of the brothers from a converted Buick, with

a plaster tiger’s head where the bonnet should be, and the horn

growls! One of the brothers name translated to Tiger; so ok they had a

sense of humour. They’d need it, visiting this lot for pleasure. The

pleasure gardens were visited by the families of the brothers for many

years, but eventually they were donated to the public. Crafty move, the

tackiness must have become even more tacky and dilapidated until the

government restored it all. It’s still pretty tacky now.

Back in the coach, Philip speaks for a long time about the Japanese

invasion, the sufferings and atrocities of the armed forces and

civilians alike. He speaks quietly, unemotionally and openly, and quite

unremittingly. He tells stories of civilians being killed for bumping

into Japanese soldiers, one woman whose baby was bayonetted because she

stumbled against a Japanese soldier and grabbed him to steady herself

while carrying the baby. Philip said she went insane with grief. He told

of the Japanese Military Police, the Kampaitai, who sounded even more

brutal than the Gestapo if that’s possible. They routed out and took

away anyone who was anti Japanese, who might be anti, or who looked as if they might be. If a civilian

looked wrong to them, or looked at them in the wrong way, they were

taken away. People taken by the Kampaitai were never seen again.

With this prelude, we arrive at the Kranji War Memorial, a beautiful

setting for war graves which overlook the city the service men tried to

defend. It is immaculate. Many rows marked ‘known to God’ start me

off, and when we get to the top of the hill and find a series of huge

walls inscribed with the names of those killed whose bodies were never

found, we are both in tears. 24,000 names from the UK, Australia

and India. We are awash with grief.

The coach takes us to the Orchid Restaurant for lunch, a set meal which

is surprisingly good, served with green tea. A little oasis in the day.

We learn that the waiters are from

China, brought here because they will work for one tenth of the wages of

Singaporean staff, which is still more than they could earn at home in

China. As their room and board is included, they send most of their earnings

back to their families in China. Seems it is the same all over the world.

Next stop, Bright Hill - Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery - a renovated and extended Buddhist

Temple

of great beauty, wonderfully colourful and the biggest in Singapore. The main Buddha, at a cost of

S$1, is probably the biggest I’ve ever seen, put in place before the

building was completed around it. The people meditating before it look

like dolls. There are 3 dharma halls each seating 1500 people, it should

be impersonal and yet it has a powerfully peaceful feel to it, as if we

are in seclusion away from the world.

The roofs are capped with dragons breathing fire, impressive seen from

ground level against the sky. The gardens are more restrained than the

buildings, with gentle lawns and small shrubs. There are vegetable

patches where the monks grow much of their own food. They are not

allowed to beg in the usual Eastern way. Philip told us if we see monks

begging for food, leave them alone, they are imposters who come in,

dress in robes in order to beg. If you give them $5, they say not

enough, the going rate is $10. Then you know they are false monks, monks

are not allowed to handle money.

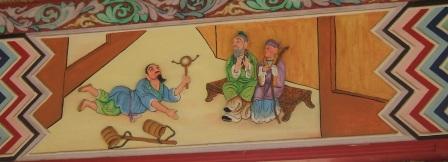

The ‘cloisters’ are decorated with panels showing aspects of

‘filial duty’. I take a picture of one to let Ben know what he is in

for – a grown up son is trying to cheer up his depressed elderly

parents, he is rolling on the floor and playing with baby toys, rattles

etc. Ben knows what he has to do if we ever get depressed!! Fun. Better

than the picture of a starving family where the daughter in law is

breast feeding her husbands mother before she feeds her own baby –

eeeughhh, what a picture!!

Nearby is the crematorium, and a large building - a columbarium - to house the cremated

remains of Buddhists. It is full, and a second, equally large, has just

been built. Nothing is high rise in this enormous temple complex, it

must cover a lot of expensive real estate. Philip tells us that many

Singaporeans wish to be buried, but the cemeteries are full and now it

is only possible to bury your relatives for 8 years. Then you have to

exhume the remains and have them cremated, so the move is towards

cremation in the first place.

Land is at a premium here, and they are constantly reclaiming land from

the sea. Vast tracts already in use, Philip points out. They have

traditionally bought sand and earth from

Malaysia

to use in their reclamation, but

Malaysia

has now stopped selling, threatened by the increasing success of

Singapore

. So they have to look further afield for their raw materials, making it

more expensive. The Singaporeans seem resourceful and unafraid of taking

hard decisions, unlike our government. The result appears to be a much

more peaceful living together of diverse elements of community, as if

everyone knows the rules and lives within them. Penalties for wrong

doing are far more severe than in the UK, which is perhaps a help too. But people feel included and rub along

together. There are, for example, 4 official languages: English,

Mandarin, Malay and Tamil. Philip described an island nation which knows

what it has to do to survive, and just gets on with it. We seem arrogant

in comparison, perhaps we don’t see our survival being threatened and

so we stumble on, never really resolving our crises. Do we even have

a 20 year plan?

|

entrance to Haw Par

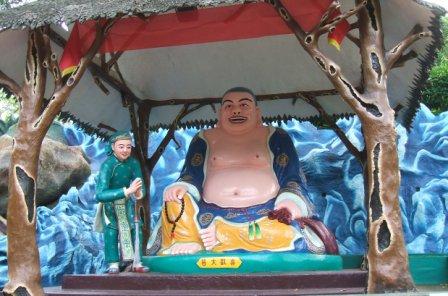

one of the more pleasant tableaux, the 'lucky' Buddha

Tiger's Buick

Kranji War Cemetery

War Graves: 'known to God'

Golden Buddha

Bright Hill Temple

Kwan Yin

one of the panels illustrating 'filial duty'

|

|

Changi

Moving on to our last stop of the tour, Philip speaks more about WW2,

and we arrive at Changi Chapel and Museum, next to Changi prison which

is still in operation. Only a derelict gate and tower from the original

notorious prison still stands, the rest gone, under protest, in the

renovation process of today’s prison. Philip says the chapel and

museum affect people differently so he doesn’t go in with us, and says

we must just come out when we want to. Some people can only get part way

round. It is unbearably moving. Much of the story of the Japanese

invasion is told in the words of people who went through it, service men

who became POW’s, and civilians. I can’t imagine how people ever

survived such brutality, or how anyone could inflict such brutality on

others. These are mysteries beyond my ken.

Changi Chapel: replica

of one built by Australian POW's

Out of respect, no photographs are allowed inside the Museum

Local people risked daily beatings or worse to help the POW’s housed

in Changi. One POW told of a woman who waited every morning outside the

gates for a work party to come through. She always had a little tray of

sweets and bits of food, not much, but some. The POW’s ate it quickly

before the Japanese could stop them, and each day the woman was beaten.

The men always expected she wouldn’t be there the next day, but she

always was. What simple courage. Any day she could have been killed but

to endure beatings willingly …. I feel humbled and unsure that I could

or would have knowingly submitted myself to that [but pretty certain

really that I wouldn’t].

The pictures speak for themselves, and I think something in the brain

switches off as you look at them because the full horror would be too

much. I wonder at the human spirit that endures and survives, more than

that, that builds something like the Chapel which is recreated here, out

of nothing. This particular one is a replica of a chapel built by

Australian POW’s, a very simple wooden structure, and today it is

pinned with notes from relatives and friends speaking about their loved

ones who were in Changi. Time after time we read that the person never

spoke of their ordeal, but that it nearly always played a part in their

death, whenever that came.

The wash of grief that threatened to engulf us at Kranji has passed

away, leaving a kind of numbness, a sense of futility and helplessness.

While knowing it is the truth, I don’t want to believe what I have

just seen and read. My mind shies away from it, my spirit feels bruised.

It is a violation of everything that is humanly decent, made all the

sadder because it still goes on today in different parts of the world.

If only we could learn.

Coming out, it is difficult to speak, not just because of emotion, but

because there seems to be nothing to say that could be of value.

Going back to the coach, I fall into step with Philip and thank him not

only for his interesting talks, but for his sensitivity to what the

museum might mean to us. He tells me that his father was taken by the

Kampaitai, and that very unusually, he escaped. Otherwise

he says simply I would not be here

today. He tells me that many of the stories he told us on the way

here were his parents stories, told to him, eye witness accounts. I

wonder what pain and anguish, what anger, lies behind the quiet dignity

with which he presents himself, but I don’t sense any. I sense

acceptance, that is how things were, this is how they are now. He does

however tell us that Japanese tourists do not come to Changi, only a few

students who wish to know the truth because this part of the war is

reduced to two lines in their text books. There is a Japanese community

within

Singapore

, they have their own school, and they keep pretty much to themselves.

It is interesting that Philip balanced his accounts of the war with

accounts of how Singaporeans live today, and I think this is in line

with what I sensed.

80% of Singaporeans cannot afford to own their own homes so they buy

government sponsored high rise appartments on a 99 year lease. The

government makes it easy for them to buy, though they can’t sell for 3

years, in the belief that it gives them something to fight for, which

binds the country together. This means that only 15% live in the

expensive luxurious condominiums we see around. There is a lot of wealth

in a very small proportion of the country.

Living mostly in high rise accommodation means it is important to be

tolerant of your neighbour, especially if you can’t move for 3 years.

Singaporeans believe it is important to have good relations with

neighbours and with neighbouring countries, and go to lengths to do so.

National Service is compulsory for men, voluntary for women. Anyone who

wants to become a Singapore National up to and including the age of 50

years has to present themselves for National Service if required.

A simple example of the way Singapore

works. Chewing gum was a problem as it has become in our towns, the

pavements were getting covered with it, it was left on bus seats and

public buildings. So the government passed a law banning the sale of it

and banning the eating of it. We could take lessons ….

The coach drops us, pretty much spent, back at Raffles. The cool of our

room and a shower revive us, though we can’t quite shake off the

feeling of dislocation caused by the contrast between the opulence

around us and the starkness of what we have just witnessed.

We go to the Long Bar to sample the Singapore Gin Sling, invented by a

barman here for a competition. It’s a plantation style room with

punka-wallah type fans, now run by electric. Each table has a wooden box

of peanuts in their shells, and tradition allows you to throw the shells

on the floor. Doesn’t seem right in a place as clean and tidy as Singapore. It also makes leaving, with even one gin sling inside you, rather

tricky as you skid and crunch on the shells.

Next door is the Long Bar Restaurant where we order steaks; wonderful

food and a quiet ambiance totally divorced from the hubbub in the bar.

It has a calming influence which I need after the day. I’m glad we

experienced it all, but Philip was right, it can be gruelling even at

this remove.

16.3.07

Last breakfast. Going to miss this once we’re home, all the fresh

fruit particularly. And those yummy bananas. This morning among the

savoury dishes on offer is asparagus, salmon either baked or smoked, and

a huge cooked ham. Wonderful, extravagant and slightly obscene.

Harvey

walks down to the river and I start my packing. Our agent has negotiated

the room until 2pm instead of noon, but our pick-up is not until 8.15pm.

I’d still like to get Ben something special, so I walk round the

Raffles shopping arcade, There are some 40 shops here, including the

likes of Tiffany’s, but there are affordable gifts too. I settle on a

wrist watch with a discreet Raffles logo, and a couple of small gifts,

fancy chopsticks etc. I find a cotton kimono for myself, with a

‘specially made for Raffles’ label. It will look as though I nicked

it from the room, but I like it and buy it anyway. Snob.

Harvey

is back for lunch which we take in yet another of the 18 eateries and

bars within the Raffles complex, this time the Deli which is packed with

local office workers. Still feel exhausted and not really hungry, just

have a pudding and tea while

Harvey

orders a sandwich that proves to be enormous. It’s cold in the Deli,

but another scorcher outside. On the way back to the room,

Harvey

takes my photograph by the sign for the Writers Bar. Snob again. It’s

fun though.

We finish our packing, get the porter to trundle our suitcases to the

lobby where they are put in store until tonight.

I’m still hankering after buying Ben a Tiffin

carrier, ornate rather than practical and having asked in the hotel

where we might see one, we take a taxi to Little India. It’s a street

of small shops selling cheap goods, liberally sprinkled with glittering

outlets for the usual amazing Indian gold. We do see one

Tiffin

carrier, cheap tin, probably eminently practical but not what I

envisaged as a gift from

Singapore

. Disappointed in the area, we take another taxi to the main shopping

street,

Orchard Road

. Here there are dozens of malls and hundreds of shops. It is heaving

with people and traffic. The noise explodes in our ears. We have orange

juice in an effort to summon up enthusiasm and energy, and make a

desultory exploration of a couple of malls. We do our best, but our

hearts are not in it, we’re too hot and tired to bother. I’m not a

good shopper any more, especially when I don’t need anything.

Another taxi back to Raffles. The economy may not have benefitted from

our shopping expedition, but the taxis have.

We can use the spa facilities to shower and change, rather more

commodious not to say luxurious than the last lot we had to use in

similar circumstances on

Easter Island

. There are huge fluffy towels and lovely toiletries including a silky

Marks and Spencers talc. My little face lights up!

Now in our travel clothes, we don’t venture far, take a few more

photographs of the hotel.

Harvey

sits regally on a huge wooden sofa with mother of pearl inlay. Then we

find it is an opium bed and he would probably have been reclining or

otherwise laid back, not looking regal at all.

We eat a light meal at the Empire Café, our last Raffles eatery. Its

local food is described as ‘hawker style’, vaguely Chinese. Don’t

like the look of the local puddings, so walk back a block to the Deli

and have a pudding and coffee there.

We sit in the lobby with the soaring ceilings, elegant double staircase

and exotic flowers. I try to soak up the atmosphere so I can conjure it

up when I’m home. All the time we’ve been here, people [not ‘in

residence’ like us] have stepped in the lobby just to take photos. I

can understand why. It is the

beating heart of Raffles, with its

discreet cashier and concierge counters, people crossing leisurely,

sitting quietly, yet it has never seemed hectic. Just a little [well ok,

rather large] oasis at the heart of this amazing legend. We've stayed in

many beautiful hotels in lovely parts of the world, but Raffles is

exceptional in many ways.

bougainvillea;

ubiquitous orchid; Singapore National Orchid: Miss

Joachim

The mini bus arrives. Our luggage appears as if by magic. One of the

giant Sikhs, one I haven’t seen before with startling light eyes,

shakes my hand till the bones grate against each other, and wishes us a

good journey. Come again he

says. In that moment, I really believe I might.

The airport routine, once tackled with mounting excitement, has become

tedious over the weeks, but this time we are travelling to our own

country so at least the form filling is absent. I’m cheered up by a

text from Ben about Mothers Day which falls the day after our return. He

is going to cook for us. It carries me through the wait.

The plane is on time and familiar, British Airways. Soon we are airborne

and the lights of

Singapore

fall away beneath us. It is one of the most uncomfortable flights we

have ever had, with turbulence for about three quarters of the time,

quite bone shaking. In spite of this, we sleep a lot of the time, as

good a way as any of passing 13 hours.

We don’t eat dinner, preferring to sleep, but after several hours I

start to feel peckish and breakfast is a long way off. By chance I

discover that Tuck Boxes are laid out in the galley and we can help

ourselves to crisps and chocolate bars. Drinks are always available, so

I’m fortified until breakfast, which is never a happy meal on board.

Omelettes and scrambled eggs do not reheat well and bacon goes soggy,

and the breakfast roll I look forward to turns out to be a croissant.

I’ve never got on terms with croissants, they are generally greasy and

nasty. The fruit and yogurt go down ok, and I resolve to have a second

breakfast when I get home. Ben will be proud of me; he and Gordon on

their exploring days, get up so early they find themselves having second

breakfast somewhere along the way.

Harvey

discovers he has packed his English money and the door key. He finds an

ATM in the airport, and we’ll have to either knock up TandeM or find

the spare key where we hid it years ago.

The last lap of our journey goes relatively smoothly. As we are waiting

for our luggage in baggage claim,

Harvey

’s mobile rings. Our ride home is waiting. We’ve done something

we’ve not done before, paid for a car to take us door to door. It’s

a luxury I appreciate at 5.30 am. after a 13 hour flight and 4 weeks

away.

Greenmead looks quiet and peaceful when we arrive. The spare key is

where

Harvey

remembered, and we let ourselves in. Home. After all the magic of our

amazing trip, right now Home is the most magic of places.

|